|

| Laurie Feinberg, Assistant Dir. at the Planning Department explains the new zoning code at Open Works (photo: Philipsen) |

Few know that the new Baltimore zoning code almost met the same fate when it still had not been adopted by City Council in the beginning of December 2016, a full eight years after work had begun on it in earnest, and more than 16 years after after reform of the 1971 zoning code was discussed as a serious need. Failure this time would not have been forced on Baltimore from the outside but would have been self inflicted.

Alas, calamity was averted.

A month after the last election with a new council ready to convene in January, the old council, with the new code in their hands since 2013 with on and off deliberations since then, found itself forced to vote the code in or lose all their work. The new council would have to begin from scratch with a first reader. Patient developers, residents and observers of the tortuous path the reform had taken since 2008, found themselves losing track in those last months of deliberations. Amendments were made and stricken in rapid order and code and maps went through a quick succession of hearings. The final bill was passed in the last minute.

|

| New designations in the new zoning code (Source: Planning) |

As Laurie Feinberg, Assistant Director of the Department of Planning ("Our Mission: To build Baltimore as a diverse, sustainable and thriving city of neighborhoods and as the economic and cultural driver for the region"). explained Wednesday in a presentation organized by AIA and APA, these "amendments" were nothing but an effort to scan through all votes of the last council and put them on a solid footing. No substantive changes to the content of the bill are allowed or included in those amendments at this time.

Anybody who doesn't design or fund developments in the city or wants to build an addition or roof-deck may wonder what all the fuss is about. Zoning? Just as exciting as going to the dentist, some may think, necessary but nothing you want to talk or read about.

To which one has to say that America is pretty much shaped by zoning, especially in all the areas which were developed after about 1920, when zoning was first introduced. Zoning even became a nefarious tool to cement racial divides. In general, original old style zoning was all about segregation keeping everything in its proper place: Shopping here, living there, offices somewhere else and industry where nobody can see it, all in the name of health and welfare. But now in our post-industrial world its all about diversity, proximity, access and equity. Clearly, to accommodate such shifts in thinking requires new rules.

|

| How the code was mapped (Source: Planning) |

Of course, much of Baltimore predates zoning and was all along more mixed-up than the suburbs that were built upon those segregating zoning blueprints. Still, anytime a project deviated from the prescribed use categories, a trip to the BMZA (board of zoning appeals) was in order, a costly affair, especially if neighbors objected. Every time a larger development couldn't be fit into the zoning envelopes, a "planned unit development" had to be devised, a detour allowing more flexibility. In the end more of Baltimore development happened in the bypass and detour mode than in conformance with the old code, a strong reason to try a fix, if for nothing else than for less bureaucracy, more transparency and easier economic development.

Some younger cities like Denver and Miami, which have to recast themselves because of massive growth, have drafted modern zoning codes that don't look at all like the voluminous legal chapters of traditional code books that are so hard to decipher because they always refer the reader to fifteen other sections. Baltimore didn't manage such a drastic break from the past (The text part alone is still 482 pages) but yet-to-be prepared electronic copies will at least have clickable embedded links that make the jumping around easier. Additionally, the Baltimore code has in the back summary tables that show all the major controls such as allowed uses, height, minimum lot area and required setbacks. The whole code book is meaningless, though, without a map that shows where which zone falls and where the boundaries are. The maps were, therefore, adopted as part of the code by City Council.

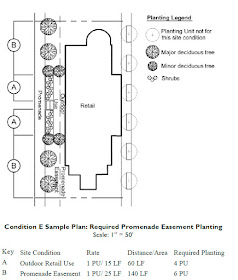

To spruce this dry stuff up a bit and bringer it closer to the expectation of a city which fosters design excellence, the new zoning code will be accompanied by three design manuals that show designers and owners what is expected for buildings, landscaping and site design. The natural desire of showing pictures of good examples had become a matter of considerable debate. Especially architects were worried that their clients would simply point to the generic pictures of the code and say "build it like that and we will have the least trouble", leading to a cookie cutter approach that would, once again, be colored by current taste and preferences. In a compromise, the design manuals were removed from the code and became standards under the review of the Planning Commission which will enact them and can also modify them more easily than the full council could.

|

| An image from the Design Guidelines (Source: Manual) |

Discussing zoning brings a minefield of conflicts. For example, once the Hopkins School of Public Health received a grant to look at zoning from a health outcome perspective, they immediately zoomed in on the many non-conforming liquor stores in the city that dot the corners especially residential sections in poor neighborhoods. The new code will force over 70 stores to be phased out over a two year period after the code goes into effect.

A perennial topic of dispute is parking. The Planning department and the Planning Commission recommended that (new) surface parking lots should no longer be allowed downtown. downtown, a provision in keeping with good urban design practices across the nation. But developers put pressure on the council to allow them this cheap way of meeting parking requirements and, voila, the Council gave itself the right to allow them as a conditional use by ordinance.

The Council also bowed to community pressure and didn't allow the conversion of large (row) houses into multiple units by right, instead requiring a conditional use permit. Large beautiful houses in areas such as Harlem Park stand empty because they are too costly and large for single family use.

|

| An example from the landcsape guidelines (Source: Manual) |

The new code is scheduled to go into effect on June 5. Before then the City Council needs to approve the clean-up amendment and the Planning Commission needs to adopt the three design manuals. Step by step the City wants to retire or let expire the old Urban Renewal Plans which had been used as one of the detours around the outdated old zoning code but as had made development even more complicated.

Then the new Council can begin to reform the new code.

Klaus Philipsen, FAIA

Text of the new code in the preliminary PDF version

Maps on City View

Design Guidelines Manual,

Landscape Manual

Site Plan Review Manual

see also on this blog: Baltimore's New Zoning - Pass or Fail?

My book, Baltimore: Reinventing an Industrial Legacy City is my take on the post industrial American city and Baltimore after the unrest.

The book is now for sale and can currently be ordered online directly from the publisher with free shipping.