|

| Old Town Mall today: Absolute desolation (Photo: Philipsen) |

On a typical day, there's nobody inside Bernie Delay's little tailor shop on Old Town Mall. No patrons. No tailor. Sprawled on a folding chair outside, waiting for business and hoping for a breeze, he comes up empty. "There's nothing doing," he says with an old man's sigh.

Old Town - a walking mall lined with weedy lots, careworn stores, Civil War-era architecture and disco-era renovations - stands frozen. Caught between Baltimore's best efforts at urban renewal, long waves of municipal neglect and the mirage of redevelopment proposals that loom just out of reach, it is a place where business owners and neighbors wait for change and wonder why. Why does the nation's first inner-city neighborhood mall - which placed Baltimore on the map for urban planners in 1975 - stands a near-ghost town today?(Baltimore SUN, July 21, 2003)

|

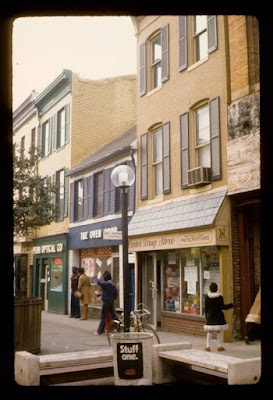

| Old Town in its first years: A lovely Main Street |

None of the many articles published about Old Town give really good reasons why an area so close to downtown, so close to Johns Hopkins Hospital, so close to Little Italy, Albemarle Square and so steeped in history should fall so far from its few years of glory after "the mall" was established in response to the 1968 riots as one of those then trendy pedestrian shopping streets which have since abolished in the US but are still common place in most all European cities.

Jesse Collins counts on 6-inch-long curled red fingernails the reasons she thinks the mall fell into ruin: Indifference. Politics. Racism. Greed. "If this was not a black mall, it would never have gone down the way it is," she says. "I'm like Forrest Gump: That's all I have to say about that." (Baltimore SUN July 21,2003)

The history of Oldtown Mall is depressing. Riots, looting, fires and a long-stalled development plan. One of the big property owners, Stanley Zarden, told me back in 1999, "Everybody that is here should get a medal."

I returned to Oldtown Mall, a pedestrian thoroughfare off East Monument Street in East Baltimore, yesterday after the owner of a Chinese carryout, Tien Zin Wang, was shot Saturday night while delivering $20 of food to what turned out to be a fake address on nearby Webb Court. (Baltimore SUN Jan 7, 2009)

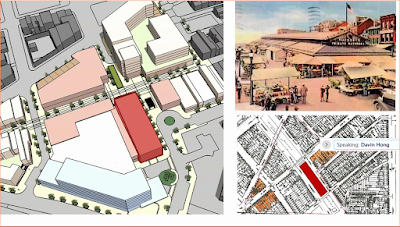

When the region’s first European settler, the Englishman David Jones, built a house on the east bank of the stream that would later take his name, the Jones Falls, he laid the groundwork for a competitive relationship between Baltimore Town on the west side of the stream founded in 1729 and the emerging rival Jonestown to the east laid out in 1732. Eventually the Gay Street bridge created the link which allowed a merger in 1745. Jones Town became commonly known as “Old Town” a name that would resurface 200 years later. in 1813 the current Old Town Mall area was the site of one of Baltimore's public markets, the Bel Air Market which was leveled in 2002 to create space for parking for a dreamed about grocery store.

|

| Old Town architecture: Eclectic mix (Photo: Philipsen) |

Old Town Mall in East Baltimore is a centuries-old commercial district that has lived through periods of booming growth, recession and renewal. Once a shining example of urban revitalization, it has since largely fallen into disrepair, with more than half of the buildings standing vacant. (Baltimore SUN, Sept 27, 2012)In spite of all this history, Old Town Baltimore has clearly not done as well as other historic neighborhoods such as Fells Point, Federal Hill, or Mount Vernon, to name just a few. Why?

The buildings themselves, though some are a little worse for wear, represent an impressive collection of historical architecture: Italianate Victorian storefronts; stout, turn-of-the-century commercial buildings; even a few diminutive two-and-a-half-story, dormered rowhouses from before the Civil War. If they were on the water or in Federal Hill, they would be filled with bistros, boutiques, and professional offices. But orphaned here in hardscrabble East Baltimore, they're dark and decaying. (City Paper, Oct 9, 2002)

Baltimore's planners and the city's Housing Department deepened the separation of downtown from the surrounding communities by arranging a number of large scale public housing projects like a ring around downtown. In many case these were high-rises that ignored the old city street grid and were plopped down as objects in modernist fashion, no relationship to streets. Most "projects" got blown up during the time of HOPE VI funding, some are still around, for example the Monument East high rise with its iconic round balcony cut outs. It sits just north of Old Town.

|

| Stores shuttered for years (Photo Philipsen) |

Now, six years after the latest development concepts were unveiled, the talk has moved to irrefutable action. The same Dan Henson who, as Housing Commissioner, had garnered record amounts of HOPE VI money to remove the housing highrises, some of which had provided the shoppers for the Old Town Mall. Now a developer, Henson has partnered with Beatty Development and others in a concerted effort of turning Perkins Homes, Douglas Homes and the former Somerset Homes area into a thriving new development. The approach is similar to the Flaghouse public housing redevelopment that has become Albemarle Square. Henson's first phase of mixed income redevelopment of the Somerset site, the McElderry apartments are now occupied. His plans for Old Town Mall have twice been reviewed by the city's design review panel UDAAP, in the latter version favorably.Some of Baltimore's most prominent developers have teamed up to work on the long-sought transformation of land near the city's historic and distressed Old Town Mall.

Beatty Development Group and Henson Development Co. are two of four firms behind a proposal to build a mixed-income community with rental and for-sale homes, a park, community center and a possible grocery store on roughly 16 acres in East Baltimore. (Baltimore SUN Feb 11, 2015)

|

| Incredible: The north end of the mall has still active retail (Photo: Philipsen) |

The buildings, 64 in all, largely fall into three architectural categories: row house shops (mostly two stories with dormers) that date to the 1820s; Victorian stores, dating from the 1870s and wider and taller than the earlier rowhouse shops; and 20th century stores that emphasize Art Deco, Moderne and Sullivanesque styles. Some of the buildings are the last in the city to have cast iron fronts. The 500 block of Gay Street was closed to traffic in 1968 to create a pedestrian walkway that the city hoped would help business.(Baltimore Heritage)

|

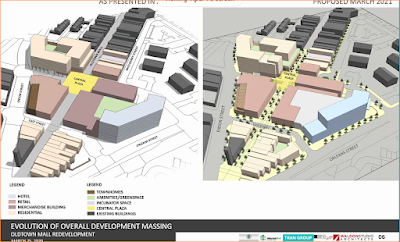

| Beatty-Henson concept presentation 2016 |

https://baltimoreheritage.org/issue/old-town-mall/

A very comprehensive City Paper article from 2002 can be found here. I am quoted in it as well