When Otis Rolley was Planning Director there was much talk about the MIZOD, anoverlay that protected industrial waterfront areas from being gentrified into condos and apartments like so many parcels before, from Harborview to the Ritz Carlton, to the Anchorage and Canton Cove.

|

| Locke Insulators: Not a trace left in the proposed plan |

But in 2017 when the Locke Insulator company announced that it will close its 24 acre waterfront facility in Port Covington (known to all Nick Fishhouse visitors who park on Insulator Drive) the loss of 108 jobs was just another blow to Baltimore's industrial base. The company's porcelain insulators used by utility companies on its high voltage overland lines was not a winning proposition anymore. Reportedly China can make these cheaper. In 2017 Port Covington was still the big next hot thing and it was generally assumed that Under Armour would snap up this site located adjacent to the envisioned new UA World HQ.

But today UA has scaled it HQ down in size and back in time to a much less ambitious suburban looking campus. And the Locke site went to Sapperstein, a developer (28 Walker Development) with multiple developments in the Canton area. When he filed for a zoning adjustment in November last year, nobody muttered MIZOD or anything about Baltimore's industrial base. No matter that not getting stuff from China any longer is all the rage. The Locke site doesn't have deep water access and was never designated as a MIZOD area, still it is concerning how easily Baltimore's industrial past gets wiped out. And as we shall see below, at times without leaving as much as a trace.

|

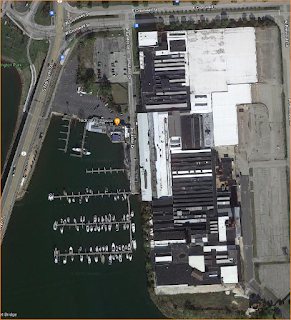

| Google satellite screenshot of the Locke site |

Today Baltimore's Urban Design and Architectural Advisory Panel (UDAAP) could see that everything about Locke was literally wiped out and made place to what one could call the suburbanization of Baltimore's waterfront. To demolish every last bit of the site's intact industrial building collection is a steep departure from many other successful Baltimore projects which used industrial shells and filled them with new uses, from the American Can to Clipper Mill, Silo Point to Seawall's teacher housing in Hampden. Each of those projects derive an attractive and uniquely Baltimore authenticity that demolition projects like Harbor View or Ritz Carlton never achieved.

Sapperstein's design team, consisting of Hord Caplan Macht Architects, KCI, and Kimley Horn, explained the new masterplan, which the UDAAP panel acknowledged, was the result of careful analysis and work.

The 24 acres are proposed to be filled with a larger apartment building and parking structure and several hundred townhomes lined up in what looks like an urban grid along the streets extended from Port Covington. Overall over 800 dwellings are proposed. UDAAP's closer analysis revealed that in spite of the urban pattern, this isn't entirely an urban neighborhood, but rather an assortment of homebuilder "products" (developer speak for their housing types) which are neatly sorted by 16' wide, 20' wide, two over-two, front and rear loaded as well as one and two car garage homes, all "products" by national homebuilder K. Hovnanian, one of the large burger chains of generic home production. Only the apartment building and clubhouse would be one of a kind designs. The UDAAP review of the masterplan will be followed by reviews of the architecture.

UDAAP members Osborne Anthony, Pavlina Ilieva, and Sharon Bradley were careful in their critique, but all of them agreed on their assessment that the proposed development was too "suburban". Ilieva suggested to "see the house types more from a pedestrian experience instead block by block". All criticized the typical way how townhome developers do the corners, i.e. by ending the two perpendicular rows of houses with exposed sidewalls "with four random windows". As an enhancement, the design team suggested on every corner a "pocket park" to fill the gap and act as a small stormwater facility. That makes four such pocket parks at each intersection.

|

| The prosed site plan (North is left) (KCI/HCM/Kimley Horn) |

Ilieva observed that "the sides ending in these corners are not architecturally welcoming", she suggested using "primary materials" on the sides as well (suburban developers always put all their expensive building materials on the front for curb appeal) "or develop a corner building". As proposed, she found that "the streets are disjointed". Reviewer Sharon Bradeley agreed and added that the corners give the design "a suburban feel". Osborne Anthony, the third reviewer had similar observations. He felt that the proposed concept did not sufficiently relate to what can be expected for Port Covington across Cromwell Street and Peninsula Drive. He called specifically the backs of the waterfront houses "suburban" for their garage driveways facing the street and producing "a lot of asphalt". "Cant you intersperse various townhome types like we come to expect in a real neighborhood, so it looks less contrived" he wanted to know. he also hope that access to the water and the promenade would not feel like "somebody's front yard".

|

| suggested typical corner treatment (top) and "two over two" townhome facades (KCI/HCM/Kimley Horn) |

Planning Department staff reviewer Tamara Woods ended the review session with the advice to "look at urban rowhouse neighborhoods how they deal with the corners and make it less suburban".

The Middle Branch is clearly the new frontier of waterfront development. The former industrial sites of the Carr Lowry glass company and the BGE facility there, also located on shallow waters, are also proposed for a large townhouse development with a very similar suburban feel.

Sapperstein, who has a large portfolio of urban redevelopments from McHenry Row to the Shops at Canton Crossing, has shown that he can do urban and suburban. Canton Crossing's success is probably based on its suburban retail convenience. This can't be transfered to urban waterfront living. Potential buyers would probably like to see something different than they can get in the surrounding counties. As Anthony observed, there are only a few opportunities of this type (of industrial conversion) left in Baltimore City. Better to get it right. A short trip to Washington's Riverfront development along the Anacostia River can provide some valuable hints and so do Baltimore's many examples of integrating our industrial heritage.

Klaus Philipsen, FAIA