Why can't Baltimore stop its decline?

Why is Charm City known for its historic architecture, its neighborhoods and its quaintness as a quirky "Smalltimore" as well as a city of firsts with the nation's first passenger railroad and the first gas light, a waterfront revitalization that became a global blueprint for industrial waterfront conversions and a ballpark that became equally influential the only city among peers that keeps losing population, Harbor East, Brewers Hill/Canton Crossing, McHenry Row and HarborPoint, Clipper Mill, Silo Point and TidePoint notwithstanding?

|

| How to get from a tangled mess to success? |

Some use psychology to explain and combat the City's shortcomings attesting Baltimore an inferiority complex and lack of self esteem. Or describe the issues in terms of family relations: Baltimore suffering from sibling rivalry with its much more famous sibling Washington DC which overshadows everything we do, even though DC was smaller than Baltimore as recently as 2010, plus it is the younger sibling by nearly six decades. Of course, there are also social explanations such as systemic racism and the large social disparities it created. In this space I will try to explain Baltimore's problems to turn around in terms of systems and feedback loops.

Baltimore isn't a backwater where nothing happens. The City continues to generate large projects that are all described as "world class", "game changers" or as "the biggest in the nation". All those projects are supposed to, in one way or another, pull the city out of its spiral of shrinkage and crime. We will set aside for a moment the mounting evidence that building big stuff isn't necessarily the right solution for societal woes. Physical projects alone won't do it anymore without having social components, such as community benefits agreements. In real estate there is much talk about impact investment and ESG. Regardless, why do these project never "change the game" in Baltimore? Why can't we pull off what Boston and DC could do, or Nashville and Chattanooga? Those cities are well beyond their tipping point and never looked back.

|

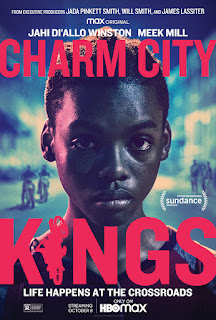

| Charm City |

Let's take a look at projects in Baltimore, then and now, and what worked and what didn't.

Duds instead of "game changers"

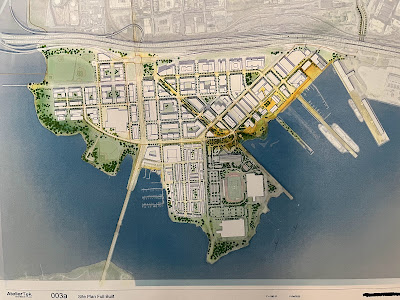

The currently most widely known mega project is perhaps Port Covington ("Baltimore's Port Covington to be the Silicon Valley of athletics wear", Archpaper, 2018), which at one point even competed to attract Amazon's headquarters. A few years after its introduction the project has already lost its luster. People are cynical about it, in part because many "game changers" before had been welcomed with enthusiasm but are almost forgotten now, because they failed to deliver what had been promised.

Remember Baltimore as a center of biotechnology with not only one, but two bio-parks at Hopkins and the University of Maryland that were supposed to put Baltimore on the map of biotechnology? ("The future of Baltimore's biotechnology industry remains to be seen. Industry observers put the city up to two decades behind the biotech hub that has taken root along the Interstate 270 corridor in Montgomery", Gus Sentementes in the SUN). Remember the concept of the digital harbor with Baltimore becoming some sort of Silicon Valley of the East with Tide Point as the catalyst? Remember "the West has Zest", a slogan to promote the revitalization of the entire Westside of downtown with the Hippodrome as a catalyst? Or recall Baltimore developer Jim Rouse's dream 30 years ago to revitalize Baltimore's then poorest neighborhood, Sandtown as an example that would guide cities across the country? The list of high aspirations tied to large projects is long. None of the noted projects went into the history books as a "lighthouse" project that would shine a path for cities to pull themselves up by their own bootstraps

|

| Game changers: Hype and reality |

Too many big projects and ideas are either limping or never made it off the ground. Baltimore's big transportation projects are a league of its own, mostly with projects that belong to the category of limping or aborted. The half baked nature of Baltimore transit projects presents a pervasive pattern that may well be called the "great Baltimore sideways slide" and stands in contrast to, for example, Washington DC's transit story which one could describe as the "great DC stepladder". Starting with the highway plans which luckily were aborted a long time ago, continuing with the Baltimore subway, the Baltimore Light Rail Line, and finally the Baltimore Red Line, each conceived to be the public transportation solution that will be a worthy successor of Baltimore's once extensive streetcar system. But none of them could save Baltimore from the reputation that it just doesn't have good public transit. Even the MARC commuter train system is at best ambivalent. The commuter trains emanating from Baltimore are said to be the fastest commuter trains in America with speeds above 100mph and are generally highly regarded, but people in West Baltimore have to board via stepping stool, the system uses diesel engines on an electrified line, and with many federal workers still not fully returned to their offices, the rail system is desperately needing riders.

Baltimore's Urban ADD is pervasive. It looks feverishly for a new topic, pulling away attention and resources before the initial catalyst that isn't anywhere near complete. The malaise is not limited to big projects. The much touted first bike-share project failed spectacularly before it ever really worked, in part because the new scooters looked sexier than the bikes and DOT was busy handling those. Both, though, require a workable and well implemented "complete streets" strategy for these modes to function successfully. The wonderfully progressive Baltimore Complete Streets policy is littered with the corpses of abandoned or badly mangled bike lanes and road diets.

|

| Pop up and no follow up |

The Department of Public Works has a massive backlog of infrastructure work, often done re-actively after a main broke and a sinkhole formed. But while all this is going on, a huge treatment facility is found to be operated incompetently with massive failures, the water billing system keeps having problems after many years of attempts to fix it, but the department focused on two very questionable mega projects of turning drinking water reservoirs into giant underground tanks. Recycling and trash pick up suffer from worker shortages. Most recently DPW had nothing better to do than design a new logo. A stepping stone approach is missing, there is no real success story to build on.

The sap of half-baked, compromised, or abandoned projects can be seen everywhere in Baltimore, whether it is in the implementation of complete streets or inclusionary housing policies (35 homes funded in 10 years), or even mega projects like EBDI that after 20 years are still unconvincing.

|

| From fanfare to nothing: Westport plans |

Baltimore's success stories

Not that Baltimore never generated mega projects that most would describe as successful. I mentioned the Inner Harbor and Oriole Park and a slew of other, smaller success stories. Successfully completed mega projects also include the redevelopment of no less than six low-income highrise districts, considered the largest HUD HOPE VI project group in the country; Those projects are, indeed notable and frequently referenced precedents. How do stalled or failed projects differ from the successful ones, what made the second set successful and the first less so?

|

| Success with follow up |

One cause of the sideways problem is the fascination with the respective next shiny toy, to revert to psychology, a sort of urban Attention Deficit Disorder that makes politicians and investors to hop onto the next big thing before the previous one has been brought to a proper conclusion. The stepladder process, by contrast sticks with a vision until it has become a proof of concept, a success on which to build and expand. In fact, successful Baltimore projects used the stepladder process, just think of Charles Center followed by the Inner Harbor, Otterbein, Harbor East and eventually HarborPoint. Or the six Hope VI projects unspooling in rapid succession, or Oriole Park followed by the football stadium.

What makes failure and what success? Transportation projects

Transportation projects provide a good set of examples that go far back and illustrate shortcomings that explain why they didn't become roaring successes: When Baltimore received federal funds to build its first Metro line, it followed right behind Washington, San Franscisco and Atlanta, all cities that completed entire systems or, in the case of Atlanta, at least two coordinate lines intersecting at a downtown hub. Baltimore had a fine system plan but argued about the first alignment and built it on the route of least resistance (in the median of Interstate 895 to Owings Mills) instead straight west where the I-70 extension hadn't been completed. The project wasn't complemented with development hubs around the stations (transit oriented development) and even at its terminus it was shunned by the Owings Mills' mall developer who didn't want transit riders have easy access to his mall. When the line finally opened it competed with a freeway in the same corridor and ran in the city through areas of decline; it didn't go where people wanted to go. Meanwhile the federal money trough from President Johnson's New Society vision had dried up and further metro lines remained a dream. To sum it up, too little, too late plus a complete lack of land use coordination.

|

| Baltimore Metro: Too little, too late |

A decade after the money for metro had dried up and Baltimore's highway projects had been defeated, the formerly highway-happy Donald Scheafer ("Highway to nowhere") switched to "light rail" as the new shiny thing that a handful of cities across the US were pursuing as a cheaper alternative to a subway: Less expensive than Metro but more effective than the small streetcars of old. The Baltimore central light rain line system was conceived as a north south line to serve Oriole Park, a single line that was not only designed but also constructed in record time. The new line had a few problems in its DNA: It hardly complemented the sole Northwest Metro Line, nor did it exactly go where the most people were. Instead it went where old railroad right of ways made it easy to build. It didn't connect with Metro in a hub and once again, there were no plans to densify development around the stations to make the line more viable and the segment through downtown was as slow as molasses.

Another decade passed before then mayor O'Malley finally wanted to get back to a comprehensive rail plan. The rail plan of 2000 looked quite like the metro plan from 1970, except it was all "light rail" but, and here the new twist, with tunnels where needed. But once the most urgent project, a real east-west line dubbed the "Red Line" was selected as the top priority its design crawled without much urgency through the federal New Starts bureaucracy which "do it now" Schafer had successfully avoided for his earlier light rail. The Red Line alignment suffered from the get-go from the fact that the original Metro Line was a east-northwest bastard which forced the actual east-west Red Line to run in parts in a parallel tunnel because light rail couldn't run in the Metro tunnel. The death of the Red Line became a nationally known planning tragedy of epic dimensions. As Governor O'Malley had failed to get this project to a point of no return in spite of a record 13 years of planning costing a quarter billion dollars, his successor coolly abolished the entire thing as a"boondoggle". The then new Governor gave the feds nearly a billion dollars back in already promised funds. Now Governor elect Wes Moore vouches to put humpty dumpty back together.

The transit saga doesn't end with the death of the Red Line: Hogan's contention that Baltimore would be better off with a full overhaul of its bus system than with one expensive rail line had some validity, except that he never meant it seriously. Hogan provided just over $130 million for a bus overhaul in lieu of the $3 billion that had been lost. The result of this bus "reform" were buses with new colors and names which right now perform worse than the old system had ever performed before.

|

| Hogan: The big bus failure |

In all Baltimore spent a whopping 40 years on creating a disconnected and unloved transit system that most describe as dismal.

How did the other cities fare that picked light rail as their future transit at the same time as Baltimore? Portland, Pittsburgh, Denver, Sacramento, San Diego all managed to build entire systems of 4-6 lines in that time, in most cases considered successes by the industry.

Baltimore's MTA not only sat on its hands for decades between completed lines, it also never nurtured the lines which in the beginning were well liked and used. Instead of cultivating a success story, the MTA presided over steady decline: The stations were neglected, signal priority on Howard Street never made it into reality and efforts of moving the stadium crowds after games soon faltered leaving fans stranded for hours. Instead of making the initial proof of concept project a stepping stone for success, it became a symbol for all that can go wrong. Even before Covid hit, riderships had fallen by 50%. Portland, by contrast supported its initial line with sound transit oriented development and careful design and soon got money for more.

When it came to the Red Line, again too much time had passed since the initial light rail line to see the project as part of the same system. Schafer's "do it now" urgency was sorely missing, culminating in the last minute relocation of an underground station which may have cost the project the critical six months which would have made it irreversible.

Yes, MTA is a State agency and not run by the City, but before folks seek all fault at the State, the City and the County also failed to implement zoning and land use changes at the light rail stations that would have supported transit, something that was a key to Portland's light rail success. The initial success allowed TriMet to build four additional light rail lines that were followed by several Portland streetcar lines.

What makes failure and what success? Grand projects

Success can also be explained with some Baltimore projects that become national models: Had the Charles Center Development Corporation waited for a decade or more to plan for the Inner Harbor instead of meticulously designing Charles Center as a successful stepping stone for the Inner Harbor redevelopment, the Inner Harbor would never had happened. Just recall that the project was nearly derailed by a referendum of those who wanted to keep an open field at the water's edge.

.jpg) |

| Step by step but upwards |

Had Housing Commissioner Henson waited for a decade after successfully lobbying for HUD funds to implode the Lafayette public highrises, Lexington Terrace, Murphy Homes and Flag House, would never have happened because HUD funds would have long dried up. But the savvy Housing Commissioner acted fast and used each project as a stepping stone for the next project, learning and refining them at each step. Clearly the last project was far superior to the first, but no project was seen as a failure.

Problem solving without stepping stones or "proof of concept" projects or initial projects that are half baked and unsuccessful is not only doomed to fail it also saps resources, ends with nothing to show and leaves project implementers or an entire city demoralized.

The successful stepping stone approach can also be seen in Oliver, Barclay and the Greenmount West, communities that have seen systematic investments by Sean Closkey's companies. His approach all but eliminated vacant buildings in each target area. The once deeply disinvested communities are beginning to attract new folks, increasing the population and the viability of support services Closkey is a strict follower and excellent explainer of the stepping stone theory in which a strategic approach brings success. The stepping stone approach is vital wherever resources are limited, because it produces a system that after initial steps becomes a self supporting feedback loop.

|

| Closkey explaining the step up process |

In summary: Success begets success. A larger multi-phase undertaking needs a successful beginning, a story to tell and resources to continue without delay.

Success and failure are closer to each other than one would think. Often small missteps decide over an upward or downward trajectory, just as a ball resting on an apex can be tipped in either direction without much effort at all.

The critical moment can be compared to phenomena known in physics: Phase-transitions, for example from rain to snow, from water to ice, or from water to steam. Before you know it the milk rises from the bottom of the pot and boils over. The shift to lasting success can come suddenly when a critical mass or energy is achieved, just like in physics. Phase transition can go both ways. Systems can collapse into a black hole that will swallow everything within its event horizon. But they can also burst out into sustained and potentially exponential growth of a sun. An urban example of such an upward explosion can be seen in Washington DC, a city which became so successful that many forget how much the capital struggled just some 25 years ago with a mayor who was arrested in a crack sting. (The Fall and Rise of DC).

|

| DC Wharf: The capital's newest development |

To turn Baltimore's downward spiral into one of success becomes harder the more half baked projects devour resources and the more projects are abandoned midway in favor of the next shiny thing. For the 36 years I have observed success and failure in this city, I had many moments when I thought that the final break thorough was right around the corner, just as it had been in Philadelphia, Cincinnati, Nashville or Pittsburgh.

On the horizon

Many big projects are still largely in the pipeline. Those include the redevelopment of Pimlico and Park Heights, a new Penn Station rail hub, a new Amtrak tunnel under West Baltimore, and a fully refurbished Middle Branch shore line. The governor elect has promised to bring the Red Line back. All this bears promise and each could become a "game changer".

I have not given up hope that eventually a competent administration will stack the pieces up so they won't tumble any longer and Baltimore could break free towards its potential. The stars are aligned, but I have abandoned any attempt of a prognosis.

Klaus Philipsen

Related articles on my blogs: