When Charles Center was shaping up it was described as nothing less than the "renaissance" of Baltimore. 33 acres of innovation and resolve adopted as an urban renewal plan in 1959, funded by bonds and becoming reality in stages, starting in 1962. A mere 60 years later, the dominoes are falling one by one.

|

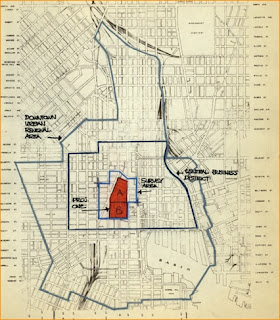

| Early concept plans of Charles Center Urban Renewal by the Planning Council 1957 (Archive of UMB) |

The Charles Center story has been told so often, it has become part of Baltimore's lore as a comeback city: Baltimore that came out of WWII still big, but mostly stagnant. Compared with today, then the downtown streets were teaming with life, shopping still happened downtown but a sense of doom hung in the air: Redlining, blockbusting, "new towns" and suburban malls fueled "white flight" and setting the stage for a shrinking city.

So, the story goes, some fearless leaders sounded the alarm, came together and formed the "Committee for Downtown". They rallied around a big plan to stay in the game. Nothing smaller than 30 acres would do in favor of a future that would boast the latest and greatest of urban renewal: Curtain wall towers, modern architecture, underground parking, pedestrian bridges and separation of pedestrian and vehicular traffic and also, revolutionary at the time, the preservation of three Baltimore landmarks.

|

| The Mies building as it presents itself today with the redesigned Center Plaza (Photo: Philipsen) |

The plan fit into a time of optimistic redesigning cities for the automobile, in Baltimore exemplified by a grandiose inner ring downtown bypass, urban freeways and one-way streets. everywhere. Not all of the love for the automobile was actually consumed, but some freeway pieces ("the highway to nowhere") and a much scaled down inner ring consisting of Martin Luther King Boulevard, President Street and the multi-lane pair of Lombard and Pratt Streets are still vestiges of that time.

High quality was expected of the downtown renaissance and leaders invited out of town big name architects to participate in design competitions. Mies van der Rohe's office was selected for the One Charles Center, a knock-off of the New York original, but still a 23 story international style tower with podium, 23' foot lobby, underground parking and a pedestrian bridge designed by Mies right here in Baltimore! The significance of this modern building was such that it was accepted into the National Register of historic places a mere 38 years later, an honor usually reserved for buildings of significance that are at least 50 years old.

One Charles Center put Baltimore "on the map" again with modern office space and all the amenities and the large floor plates the time demanded. After One Charles Center a whole cluster of towers followed! When the new offices were successfully filled, it was only natural that the spirit of rejuvenation expanded to the Inner Harbor to turn the smelly waterfront into an urban playground.

D'Alessandro, McKeldin, Schaefer, Rouse, Millspaugh and others were the heroes of the time, along with the architects David Wallace, Charlie Lamb from RTKL and of course, Mies. The completion of HarborPlace was the bow on Baltimore's renaissance which became a term among planners around the country that brought hotels, conventions and even tourists.

Such is the well rehearsed lore, it's hard to believe that all of this should be over now, even when we could see the trophies of that time fall one by one: Down came the pedestrian bridges, the Mechanic Theatre, the McKeldin Plaza and the whole notion of separation between cars and pedestrians. It got really bad when the rot spread from Charles Center to the famous pavilions at Harborplace. The Mies Tower seemed to stand tall and unmutable. Until the Angelos empire began to unravel, that is.

|

| The former Burger King now the AIA Architecture Center (Photo Philipsen) |

Now with the feuding Angelos clan holding a fire sale (will the Orioles be next?), Charles Center comes into focus as a mere ghost of itself more than half empty surrounded by other failing towers already have changed hands and heading towards a far less glorious reincarnation as apartment towers, no matter how often the term luxury is stuck in front of the word apartment. The conversion of the central business district into a fast growing residential neighborhood is the new narrative of success.

The whole notion of downtown is very much in question again, not only in Baltimore, though. This time there are no big renaissance plans in sight. The Downtown Partnership is in search of a "blueprint".The future is is in question.

Opinions about the future of downtowns vary, fact is that office workers are returning only slowly and office vacancy rates are on the double digits in many other downtowns, for example Philadelphia. This doesn't stop Richard Florida to editorialize in Bloomberg's City Lab that Downtown Won't Die, but his optimism is of little help for downtown office tower owners or those whose retail needs the office workers, nor will it help city coffers. Downtowns on average cover just 1-3% of city land, but they provide 10-30% of the tax revenue. The optimists from Stantec to Richard Florida and Baltimore's BCT principal Bryce Turner who may be redesigning the Mies building for residences see no big problems with converting the shiny office towers into residences. But it won't be easy for those offices built during the age of urban renewal where a single building often covered an entire city block and where deep 40,000 sf floor plates where all the rage. No matter that the facades may be mostly glass, once one is about 50' away from the facade, there is no further stretching habitable residential spaces any further back into the deep buildings and still have the required daylight and ventilation.

|

| When planning didn't produce big glossy plans but actual buildings in short order (UMB Archive) |

The coronavirus pandemic has exacerbated challenges facing Baltimore’s downtown core. Commercial vacancy rates have grown into solid double digits as major tenants and jobs move to newer properties outside of the city center. But at the same time, the conversion of commercial buildings to residential properties has made Downtown Baltimore one of the fastest growing and most diverse neighborhoods in the city. Still, these residents lack the stores, green space, restaurants, public safety and entertainment venues they need and deserve.(DPOB "The Future of the CBD")

How can an urban intervention go from being cutting edge to obsolete in only 60 years? Weren't cities meant to be good for the centuries? Where did we take the wrong turn or is Baltimore in the same boat as any other US city?

It turns out that pretty much everything that was all the rage in urban design in the 1960s turned out to be wrong, whether the fathers were Ed Bacon (Philadelphia) or David Wallace (Baltimore). At least from today's perspective. The modernist freestanding towers (think for example the USF&G Tower) ignored pedestrians and streets with their windswept plazas and pristine but dull entry lobbies, guiding pedestrians on elevated walkways, turning Charles Street into a service alley for garage entrances and service ramps, and, worst of all, the mono culture of offices over offices which turned out to be giant energy hogs with poor insulation. The glass facades caused the interior spaces to heat up in the glaring sun without help from operable windows and required mechanical cooling and ventilation year round.

All those issues turned out to be deadly for a lively downtown and as a result those towers are no longer popular as offices, nor are they especially suitable for residential conversions, at least not without major and very costly surgery.

Hindsight is cheap, and those who are old enough to remember the excitement about Baltimore's renaissance through modernism (including me) will certainly object, that the Charles Center masterplan was not all that bad. Indeed, one can point to a number of innovations that were not common in the 1960s and that pointed in the right direction: Charles Center included open spaces such as Center Plaza which needed some softer redesign but were very much needed in an otherwise crowded dense setting. As noted, three remarkable structures were saved (including the B&O headquarters and the Fidelity Building) and the plan had a residential component with the apartment tower on Saratoga Street and the associated small shopping center. The plan even included with the Mechanic Theatre an entertainment comonent that became famous for its sculptural concrete architecture. Furthermore, the project was executed fast and efficiently through a series of private investors and set high standards for design.

|

| The shameful wasteland that once was the Mechanic Theatre, right in the heart of downtown (Photo Philipsen) |

When we have to witness that even the flagship building, "the Mies" is no longer a desirable destination, let alone a premier address were the most notable law offices, insurers, architects and others want to be we can bemoan that once again we do not cherish our own history. 51% vacancy attests to the rapidly changing preferences that sometimes seem to see cities as objects that can be changed like a wardrobe..

Luckily, the building has a peristent elegance that some of the other towers that came after it don't show. The comparably shallow floor-plates will make a residential option easier than in some of those massive squat towers. Still, the new mantra of converting so many office towers into residences could easily create another mono-culture and glut, especially in a shrinking city such as Baltimore. Those who already live downtown, in spite of their impressive number continue to miss the hustle and bustle that downtown living brings in DC, Philadelphia, New York or Boston, all cities that continue to grow and also seem to recover faster from the pandemic than Baltimore.

All who care about Baltimore need to ask themselves, how the downtown of the future should look like. A downtown that remains a destination for the region at day and at night and a downtown that is an attractive neighborhood as well. Such a downtown can only be resilient and interesting if it encompasses live, work and play in equal parts, to use this somewhat overused troika of verbs. And more than anything, Baltimore's downtown needs continuity of functioning and active blocks without the big gaps of boarded up and unsafe zones that downtown residents and workers encounter as pedestrians in almost any direction they want to go, whether on the way to the Hippodrome, the soon refurbished Arena, the soon to open new Lexington Market, to and from a subway station or going to the newly refurbished Rash Field, the brand-new HarborPoint or hostoric Little Italy, Fells Point or Federal Hill. The most resilient downtown areas are those that never became office or shopping mono-cultures, in Baltimore and in many other cities. Jane Jacobs had it right all along.

Klaus Philipsen, FAIA

Baltimore SUN about One Charles Center