|

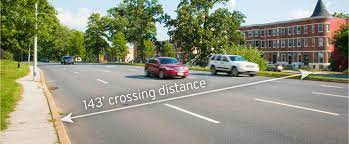

| Car centric design: Lots of space for cars, little for pedestrians. (Image from TAP, |

|

| Druid Hill Park: An asset chocked off by roadway barriers |

Baltimore's Druid Hill Park ranks with distinction among a very short list of large historic urban parks in America. With a pastoral landscape, picturesque reservoir and even the Maryland Zoo, it is a popular destination for not only Baltimore residents but also for visitors from the surrounding region. Yet somehow, its bordering neighborhoods have not benefited from being next to such a landmark amenity. They have not thrived as sought-after communities and are instead deserts to recreation, greenery and quality of life.Shortly afterwards, Daniel Hindman a community member and physician, added the equity and health angles in another SUN editorial

Certainly, there are many complex factors that shape the health of communities and that make their success so elusive. But there is one very obvious reason why Druid Hill Park does not contribute to its surrounding neighborhoods: It is bordered by very wide, fast streets that act as physical barriers, separating the park from its surrounding communities as a green island among a sea of asphalt arteries.

|

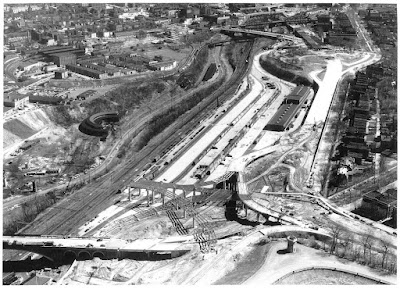

| This photo of the construction of the JFX shows the extent of impact urban freeways had |

While many know of the racism of the park’s past — the segregated swimming pools, tennis courts and playgrounds — many do not know the politics and history behind the construction of the Druid Hill Expressway. The story of the expressway’s construction is a narrative of racism and corruption, that, like an arrow shot from the past, inflicts damage on our most vulnerable populations today. ...The impact of this history is evidenced today in the 2017 Neighborhood Health Profiles, which demonstrate that Reservoir Hill and Penn North, communities that border one of the largest urban parks in the country, have some of the highest rates of cardiovascular disease in the city.

As Director, his top priority is to focus BCDOT's efforts on initiatives that better serve all users of the transportation system to improve walking, biking, transit and driving in Baltimore (DOT website)

|

| Overpass over the JFX at 28th Street before the "Big Jump": Little room for pedestrians, fast moving traffic |

TAP Druid Hill is a coalition of residents, city officials, and community partners working together to increase access to Druid Hill Park for people on foot, wheelchair, transit, and bicycle / escooter. (website)

While the Druid Park Lake Drive corridor borders the United States’ third-oldest public park and beautiful historic neighborhoods, the roadway is designed with the characteristics of a highway, rather than a neighborhood-scale roadway. Originally a two-lane residential street, the current alignment of Druid Park Lake Drive is now a 4-to-9-lane arterial road that carries high-speed vehicle traffic, lacks safe pedestrian, bicycle and transit infrastructure and effectively creates a barrier between neighboring communities and Druid Hill Park.

That the streets are also seen as a battlefield for equity and social justice just heightens the tensions. DOT's Druid Lake Park Drive report ("The Report") says:

|

| Councilman Pinkett (speaking), Mayor Pugh in 2018 at the Big Jump opening party (Philipsen) |

The neighborhoods bordering Druid Park Lake Drive are predominantly Black and have experienced generations of disinvestment, racial discrimination, poor public health and decreased quality of life [....]

Equity is a driving factor for the redesign of Druid Park Lake Drive, and ensuring access for all modes, ages and abilities is a key component in creating an equitable corridor. Demographic data for the area within a half-mile and quarter-mile radius of the corridor illustrate what equity means in the context of Druid Park Lake Drive. Of the 88,000 people living within a half mile of Druid Park Lake Drive, 30 percent live below the poverty line, 22 percent live with a disability and 93 percent are people of color.1 Nearly half of households living in the neighborhoods around the Druid Park Lake Drive do not have access to a car. These community members get around by walking, cycling, using wheelchairs, riding scooters and catching transit. Building infrastructure to allow these residents to safely use Druid Park Lake Drive is key in advancing equity.

After several initial community participation meetings DOT developed a vision:

We envision a reimagined Druid Park Lake Drive that is safe, built for the human scale and accessible for all ages, abilities, and modes of transportation. This future corridor will closely align with the City’s Complete Streets principles, while creating a functional, vibrant, and aesthetically pleasing roadway that reclaims roadway space to re-establish safe multimodal connections between surrounding communities and the park and embraces the area’s natural beauty and historic significance. Through the redesign of this corridor, we aim to elevate health equity, allow communities to support aging in place, and support expanded transit service to Druid Hill Park.The community based approach, the outreach, the grant funding, the problem definition, the experiment and its evaluation were all great moves. But where are we now?

|

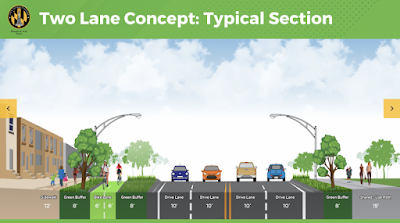

| One Lane option and bike/ walkways: 779 votes (DOT) |

|

| Two lane option: 170 votes (DOT) |

We are citizens dedicated to fighting efforts to alter city streets in ways that promote traffic congestion (Facebook page)

The group has blanketed the neighborhoods with yard signs and dubious messages against bike lanes on Gwynns Fall Parkway (part of an envisioned big bike-ped loop around Baltimore) and on Druid Lake Park Drive.

The bike lobby Bikemore and the car lobby Save our Streets called upon their followers to weigh in on the three design options which were polled early this year on DOTs website. Neighbors, of course, voted, too. The results are very clear: 779 votes opted for Option 1 which proposed only a single lane of cars in each direction, 170 voted for option 2, with two lanes of traffic in each direction. Only 15 votes for a hybrid option with 2 driving lanes in one and 1 in the other direction.

|

| Save Our Streets coalition poster: Free to drive |

In this culture war reason was winning. Luckily the future design isn't really decided via open polling. Ex-councilman Pinkett's foresight of organizing local stakeholders and putting them in the "driver's seat" (or into the "Big Jump") pretty much ensures that nearby residents will have a voice when it comes to what gets implemented when. . The engineering evaluation showed no downside to the preferred single lane solution, neither in modeling nor in the real world application. So what stands in the way of implementation? Why is the project not funded for construction, in spite of all the extra federal funding for infrastructure and Covid recovery? The current capital improvement program (CIP) shows no money for the project which is estimated to cost around $30 million in all. It isn't too late to amend the CIP. It is not too late to comment on the DOT report . The comment period for the ends this week Friday.

Bikemore director Jed Weeks observes that the drawings for the three options are not yet the 30% design level that usually justifies the first tranche of implementation funds. Even when funded, it will take long enough to build the project. William Ethridge, the DOT planner for the project, estimates that it would take 5-7 years to get the project completed, once money is set aside, that is.

Now is the time to "jump" into implementation. Maybe it takes a decision of the Mayor to finally implement this project and signal that once and for all, Baltimore's transportation paradigm has shifted.

Klaus Philipsen, FAIA

Related on this Blog: What is the Big Jump all about?

No comments:

Post a Comment