The entire Southwest Baltimore County political echelon including House Speaker Adrienne Jones was assembled when County Executive Johnny Olszewski announced that $10 million State and $10 million County money would be set aside for investment at this ailing 100 care mall site tucked in between I-695, I-70 and Security Boulevard. Olsziewksi described the mall as a one thriving hub which he imagined to turn again into a "world class shopping center and and community hub". To help matters along, the County will retain architects and planners to guide a "community driven design charrette".

|

| County Executive Olszewski announced $20 million for Security Mall (Photo: Philipsen) |

The backdrop for the open air press conference were some back hoes and the remnants of an old Bennigans and I-Hop which had sat as abandoned eyesores along Security Boulevard for years. A couple TV stations had come out, and the print media took notes.

Speaker Jones, who hails from the area, noted Security Square Mall still remains a vibrant place for many local businesses and an important part of the community. She observed that the communities of the Southwest have often reminded her that the property needs significant revitalization and investment. “This $20 million investment will jump-start this effort and help bring new life to the community.”

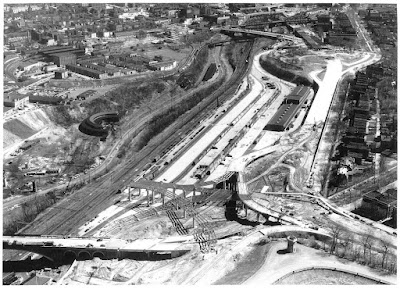

Council chair Julian Jones recalled the year 2015 when the construction of the $2.9 billion Red Line should have started with a stop "right here where I stand", Jones said. "That would have brought investment to this mall, but now we will do what is necessary, he said and thanked the Executive and the Speaker for their efforts of securing the funds.

|

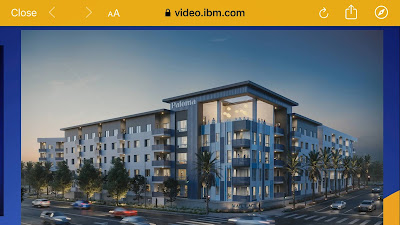

| Mall redevelopment with housing in Santa Ana, Ca |

Of the 5 mall owners only the latest operator spoke, the pastor of the "Set the Captives Free" church, Karen Bethea, introduced as "a force of nature" spoke. The church has bought the former JC Penny wing of the mall and operates community outreach, education and soon a daycare center in the mall. The possibly most outspoken and powerful owner, Howard Brown, was not present. A few years back he was the first to publicly present the idea of a new mixed use town center on the nearly 100 acre mall property. He was convinced he could strong-arm the other parties into his vision. Albeit, this didn't happen.

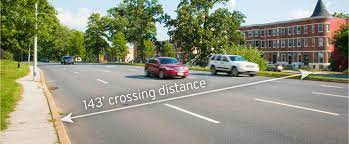

Brown thinks little of the replacement of the abandoned I-Hop with a new Chick-Fil-A, planned in the same location. This plan follows a defeated gas station and is seen as an improvement by some who are tired of the abandonment and trash. However popular, in terms of urban design and land use Chick-Fil-A is not different from the other 1-story drive to or drive through "pad uses" that ring the mall. Those structures will simply be in the way if the NAACP's Task Force preferred vision should be realized which was developed with strong community participation. The preferred scenario envisions a mixed use urban village with a "main street" lined with higher end retail, market rate housing, some offices, urban parks and civic uses.

The NAACP vision was not mentioned in today's press conference, and none of the task force members got to speak about their vision. Instead, the Executive spoke of "a blank slate". Mall redevelopments around the country show, that conversions of old malls into vibrant towncenters don't happen easily, and certainly not without strong leadership. Ryan Coleman chair of the Randallstown NAACP and Danielle Singley, the Task Force Chair know how difficult it is to unit people behind a common goal. Both were at hand at the press conference but stayed in the background.

|

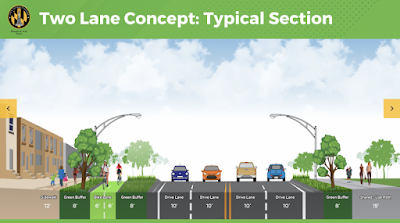

| Demand for retail space is declining while housing needs are unmet (From a mall redevelopment presentation) |

Especially since communities around the mall have already spoken in an at least preliminary manner, there wouldn't be anything wrong with County leadership uniting around the concept of a mixed use center which would not only provide much better services for the community but also provide jobs and become and economic engine in the area which has seen declining school performance and increased crime.

A $20 million investment is a great start if the money is used as a seed to facilitate that all stakeholders rally around a new vision. With potentially millions of additional square feet of use (the current mall on a mostly vacant lot covers an area of about 1 million square foot of use area) nobody would have to fear displacement. Lots of "stuff" could be developed on the vast parking lots long before any part of the mall would have to come down and there would be still room for green open spaces and parks.

Experiences from other redevelopments show that a new masterplan should not only be developed but must also become legally binding. Public investment in the roads and the infrastructure needed for a new town center could facilitate the creation of fully "entitled" development parcels. Ready to build development parcels right at the Beltway would attract new investors and wake up the current mall businesses from their slumber. In this manner the County-State funds could, indeed, become the first step for a new community hub that is also an economic power-house.

While the new masterplan is being developed in the "charrette" process starting sometime this year, no new development should be allowed in the interim. However, it seems not only Chik-Fil_A is an offender; the County administration itself is already creating new facts on the ground with a new $1.2 million 8.8 thousand square foot community health center planned in collaboration with the church. Not helpful, should the masterplan recommend that the mall should be leveled, as for example, at the old Rockville Mall in Montgomery County.

With new elections for a Council and Executive with the seat of district 1 vacated by Councilman Tom Quirk, champions of a radically new development model can yet emerge. All three candidates vying for Quirk's seat were present at the press conference today.

Olszewski himself, whose seat is safe, when asked about a development moratorium during the planning stage responded: "Speak with the Council!".

Klaus Philipsen, FAIA

Previous mall articles on this blog:

How the failed Security Mall could become a thriving town center (July 2021)

Howard Brown plans second County Town Center (March 2017)