The last time Baltimore became famous for innovative urban design was for the reclamation of its waterfront and for Oriole Park as a downtown ballpark. These two wonderful assets, however, both suffer from a common malady: They are isolated by wide and nearly impenetrable roadways that defiantly keep the core ideas of these designs from coming to fruition.

|

| Too many lanes in each direction: Pratt Street at Calvert Street |

The Inner Harbor, the older of these innovations, clearly shows that it is suffering from bad connectivity. The ballpark, shoehorned into an existing road network, less so, no matter the highway obstacles on the east (I-395), the south (the MLK ramp), the north (Pratt Street and the west (MD 295).

As I have described in this blog before, Ashkenazy, the current Harborplace owner, is investing in a redesign of the aging pavilions. The City does its best to put events there. The recent Light City Baltimore brought tens of thousands of Baltimoreans out to the shores they usually leave to the tourists.

But what if tourists and residents decide that they don't want to be confined any longer to the shallow territory along the promenade? That they have seen enough Cheesecake Factories, Bubba Gumps and Ripley's Believe it or Not, generic places one can find almost anywhere? Clearly, current progressive urban planning would want the waterfront to support our authentic and partly historic downtown and neighborhoods and conversely have downtown and the neighborhoods bring energy to the waterfront. True synergy, just as it works so well for Harbor East and Fells Point.

|

| The choking highways around the City's key attractions |

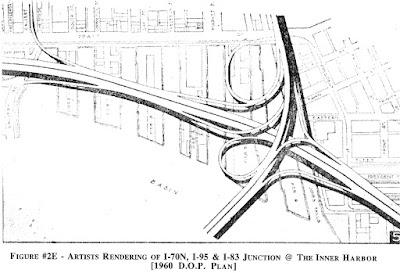

In fact, these highway style roadways represent what is left of the failed dreams of elevated interchanges that would have connected I-83, I-95 and I-70 in a giant bowl of spaghetti that would have wiped out all of our currently most successful areas: Fells Point, Federal Hill and the Inner Harbor along with all the successful new areas such as Harbor East, HarborPoint and Canton.

Does it make sense that Baltimore still feeds that beast that would have almost destroyed Baltimore with 10 lane "streets" after the City's loins were successfully ripped from its teeth?

|

| Light Street at Key Highway |

For those who use these big roadways every day, it may have become normal to see the vast expanse of concrete, see the brave pedestrians trying to cross between 6 and 10 lanes of traffic, see the enormous amounts of vehicles trying to tightly squeeze around the very corner that our brochures tout as the City's key attraction?Harborplace is the City's 100% branding spot and yet cut off like a disliked stepchild.

Ultimately, the grandiose roadways around the Harbor all have to surrender to the normal Baltimore reality of historic streets that are one or maximally two lanes per direction: President Street becomes Aliceanna or Fleet Street, Light Street becomes Calvert or St Paul Street, only Key Highway can pride itself to be equally inhumane from end to end.

Far from being the first to have recognized the issue, bright brains have addressed the issue on how to make these roads more urban for decades. But nobody has looked at all of the at once, i.e. that entire bloody U that chokes off the harbor. More importantly, almost nothing has been done to mitigate the problem except for a few small cosmetic changes here and there such as the conversion of a former bus trolley lane to a combined bike and ped trail.

|

| Pratt and President Street |

The most refined re-design for Pratt Street was then prepared by Ayers Saint Gross Architects in 2008. Like Preston Gardens, the initiative came from the Downtown Partnership. However, the ASG plans were first watered down from a two way street with median to maintaining the existing roadbed as a one-way street and then languished except for some isolated improvements in the sidewalk areas. Right now more drastic road diet elements would have to be initiated by a new mayor and an invigorated city department of transportation.

The biggest idea, connecting the McKeldin Plaza to Harborplace by closing the "dogleg" roadway that connects northbound Light Street over to Calvert Street, is pedestrian friendly but a nightmare for traffic engineers. So the City decided to have it studied by traffic engineers, handing the henhouse to the fox. Nobody should hold their breath for an outcome in favor of more people connectivity, unless a bold, daring Mayor and Director of Transportation would take the reins.

ASG also did a more comprehensive re-do of the area dubbed Harbor 2.0 but that masterplan didn't make the entire U of Light Street, Key Highway and Pratt Street people friendly either.

|

| The insanely wide Light Street west of the Harbor (10 lanes) (photo Gerald Neily) |

When these streets were initially designed, downtown was a one-trick pony (a single use office burg). There my have not been all that much of a need for strong connections and true to the ideals of the time, pedestrians were separated and there were these pedestrian bridges for them that are now slated for demolition.

The gripe isn't so much with the original design but the fact that the bridges come down without an alternative. The City is still putting up with the car centric design when today downtown has become a neighborhood with thousands of residents and Harborplace should increasingly be seen less as a shopping mecca and more as a community open space that needs to be seamlessly connected to downtown, Otterbein, Federal Hill and Sharp Leadenhall. For that all those roadways need to be reduced in width and be redesigned as urban streets instead of suburban arterials.

To become a city of the 21st century Baltimore has to become a

|

| Pratt Street a while back but essentially unchanged (photo Gerald Neily) |

While this is mostly a social, economical and political challenge, the ubiquitous road barriers are not simply accidental but they are a sad manifestation and symbol of obsolete and often obscene policies of the past. As such they go far beyond transportation and lie at the heart of what vexes our city in so many ways.

Klaus Philipsen, FAIA

updated

Links:

Gerald Neily's piece about Pratt Street

ASG Pratt Street Plans

EDSA competition renderings

Next inthis series: The ultimate insult: The Highway to Nowhere

This series about Baltimore road follies will be complemented by the weekly blog on Community Architect that will be published this Friday: "Now Federally recognized: The US Highway Injustices".

|

| 1960 Interstate Plan: I-70 weaving down what is now MLK and going East along Pratt |

|

| 1960 Interstate Plan: Harbor Interchange near Pratt at I-83 |

|

| ESDA competition design (Pratt Street) |

|

| ESDA competition design (McKeldin Plaza) |

No comments:

Post a Comment