Baltimore's single route light rail with its 30 miles of track is theoretically the easiest train system to operate: Go from A to B and then back with two spurs allowing certain trains to turn into BWI and Penn Station.

|

| Baltimore Light Rail: Running back and forth on a single route (Photo: Philipsen) |

With train speeds of an average of about 25 mph the 30 mile end to end trip is scheduled to take 80 minutes. Over 50 available light rail cars provide enough rolling stock to populate the route with two car trains every 10 minutes in both directions all day long, including layover times and spur runs, still leaving a reserve for cars to stay in the shop for repairs. Two maintenance facilities allow to dispatch relief trains from two ends in case of disruptions or breakdowns.

With a system that has almost everywhere two tracks and sufficient crossovers, it should be possible to bypass stranded trains or do track maintenance without service disruptions.

But a combination of underfunding, poor maintenance, poor operations and convoluted regulations have managed to give riders a very different experience for many years to the point that this simple system became completely dysfunctional. Covid was just the last challenge that sank the long leaking ship.

|

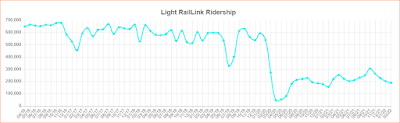

| Light Rail ridership this century: Down (MTA webpage) |

On June 5 this year with baseball fans finally back in the stadium and enjoying a game, the trip home via light rail turned into an ordeal. Trying to get home would be riders stood on Camden Yard's platform and waited, and waited. The Next Train announcement board remained stubbornly black for a 20 minutes and finally sprang to life with a southbound train expected in 42 (!) minutes, longer than Sunday headways even without a game. A quick check on the app showing trains on the system only showed three trains on the entire 25 mile line, two right behind each other going north and only one going south, it was still in Hunt Valley.

|

| Deteriorated embedded track in downtown (Photo: Philipsen) |

On July 5 a traveler posted on Facebook a similar plight for people waiting for a train to take them home from the airport. Here, too, there was no train listed at all and then one was indicated still 40 minutes away. A great welcome for a tourist or visitor coming to Baltimore and being excited that there is a direct rail transit option for getting to downtown.

This year these two incidents were not outlier experiences but representative of a new normal at Baltimore's light rail system. Even though it was clearly known to the administration, the situation did not elicit immediate and swift remedial action and not even communication with riders. In the full month between these two events the service had neither improved nor were riders made aware of the situation with posters, online message, emails or in any other way. The gap between the enthusiasm and belief in good transit exhibited by leading MTA staff and the actual service out on the ground continuous to be a source of amazement for any observer. One has to conclude that the willing folks at MTA are held on an awfully short leash by MDOT under which MTA operates.

Finally, on June 28, the MTA came out with a press release and with a single culprit: A lack of train operators. The remedy: Service cuts.

"In response to a shortage of operators, the Maryland Department of Transportation Maryland Transit Administration (MDOT MTA) today announced a temporary adjustment in Light Rail service to align service levels with operator availability and ridership, which remains low compared to pre-pandemic levels. Beginning, Sunday, July 10, weekday trains will operate on a modified Saturday schedule. There is no change to weekend schedules. This temporary service adjustment will ensure that Light Rail riders have a schedule they can rely on. (Press release)

But folks arriving at BWI and judging the Baltimore region by the first impression they get when trying to use the train transit option at the airport had no way of knowing that the Maryland MTA had more problems than other transit agencies in the country, and given up providing reasonable train service altogether. The same was true for travelers arriving at Penn Station with no obvious info that the spur wasn't running (See this video from April of this year). Visitors to Baltimore (yes, they still exist!) will still be unlikely to find out on MTA's website unless there is actual information posted at the station.

|

| Train stranded due to icy wires (Photo Philipsen) |

MTA has finally begun to react to some of its longstanding practices that contributed to the operator shortage: Such as the union negotiated practice of considering light rail as an awards program given to senior bus operators. Apparently the prestige of a train was considered a perk, even if route picks on light rail are essentially impossible since there is only one route to pick. Reportedly MTA and ATU have finally agreed that hiring outside operators would be acceptable. Needless to say, before improvement from new hires can be felt, a lengthy training period needs to be successfully completed and staff to do the training is also needed.

“We recognize the critical role that Light Rail and transit in general play in the lives of our riders. While we are disappointed that we have had to take this step, these temporary adjustments will ensure our riders can count on their scheduled train arriving on time. We are working diligently to return to our normal service level.” (MDOT MTA Administrator Holly Arnold)

True, less frequent trains are more acceptable than ones that don't show up at all. Still, to understand how operator shortage can lead to a full collapse of the schedule one needs to see that Baltimore's light rail problems began long before the pandemic. There were wheel problems and there were shelters where the glass remained busted out for months. LRT was the last to get onboard GPS and real time train location. The ticketing system remains complicated, especially if one has a day-pass. Downtown trains remain extremely slow, in part because of uncoordinated signals and in part due to a horrendous condition of the tracks. The train midlife overhaul took many cars out of the system. Track repairs shut the system down time and again forcing people on to "bus bridges". Other problems are not of MTA's making: The trains run on top rickety infrastructure. A tunnel fire underneath light rail closed the street for a week. In one case part of the station platform disappeared in a sinkhole. Land use near stations has never seen a coordinated push towards intensified, "transit oriented" development.

As a result light rail managed to lose riders ever since a peak of ridership of around 30,000 per day after the grand opening of the system in 1992 when trains were the pride of Baltimore and ran on schedule most of the time. The capacity of the system could have easily reached 50,000 riders or more a day as other single line cities such as Houston, Seattle and Phoenix showed, even before they expanded their single lines to truly become systems.

Expanding the single route light rail line is a a feat that Baltimore never managed to do. After 20 years finally a second light rail line was planned to augment the north south line with an east west line. It took 13 years and $250 million to bring this second line to a shovel ready level of design when the current governor pulled the plug on the project, forfeiting almost $1 billion of federal funds. Now, 40 years after the first Baltimore modern street-car began operating, no additional light rail project is in sight.

|

| Large cars, large capacity for post game hauling (Photo: Philipsen) |

This is the worst time for a public transit system to collapse: The urgency to act on climate change has never been greater. The transportation sector with its 40% contribution to greenhouse gases offers ample room for improvement, in an urban area chiefly through transit. Transit agencies around the world are struggling to get riders back after COVID kept up to 70% of riders out of trains and buses, either because they worked from home or for fear of infection. To its credit, MTA kept most of its service intact, in spite of COVID so that essential service workers and transit dependent users would not be stranded.

Driver shortage is an issue around the country for transit agencies and school bus operators alike. Yet, other transit agencies tried to be in front of the problem, mostly by adjusting their spring 2022 schedule to reduced ridership and availability of operators and by offering significant sign-on bonuses to attract drivers. MTA seemed to be caught off-guard to an extent that their pledge looks quite ironic:

The State of Maryland pledges to provide constituents, businesses, customers, and stakeholders with friendly and courteous, timely and responsive, accurate and consistent, accessible and convenient, and truthful and transparent services. (MTA Service pledge website )

Covid or no Covid, the airport trains are always waiting at the platform at Denver's airport. Trolleys and trains in Philadelphia, Boston or DC provide reduced service but without major disruptions. Transit systems around the world also experiment with free rides, reduced and simplified fares (WMATA, Boston, NYC MTA) and with a host of communication improvements in an effort to lure people back to transit.

The federal government packaged new transit money into the Infrastructure Bill and issued a whole compendium, academics posted papers with advice how to recover in and after the pandemic. A concerted MTA effort is not visible.

To the contrary: While MDOT orchestrated a gas tax holiday, it increased transit fares on July 1 per a mandated routine adjustment law as if no problem existed. There is no special investment in sight, that would lure riders back, no matter that this would be the age of transit when gas prices are skyrocketing. In Germany a federal initiative that brought a $10 flatfare monthly transit pass to all metro regions acrosss the entire country found 16 million buyers in the first three weeks (The campaign will run for three months). MTA, by contrast, breaks its "pledge" every day. Its services are neither timely, responsive, consistent, nor transparent.

Excuses for poor performance are numerous: Too many signals in downtown, cars on the tracks, crashes, broken limbs or ice on the overhead catenary, overhaul of tracks and vehicles and even overcrowding after ballgames.

It shouldn't be that way. The LRT system was originally designed to deal with all of these problems. For example the MTA has a diesel engine that can push stranded trains in icy conditions and brush off the ice from the wires. But some things never got properly implemented, for example signal priority on downtown streets. Other assets never came properly to bear: MTA operates North America's largest vehicles, wider and longer than anything else, made for peak demand, for example before and after stadium events. The Camden Yards Station has a tailtrack to store additional trains, if needed it could be lengthened. The football stadium has its own elaborate station. All stations were designed for three car "consists" that are a whopping 297' long.

Still, post game operations have been a problem for decades. Complaints of crowded stations and trains, excessive waits, and even of fans being stranded altogether have persisted over the decades. Three car trains were rarely used after William Donald Schaefer, the father of the Baltimore LRT system, was no longer Governor, not even at events. Lately the MTA runs single car trains most of the time.

|

| Howard Street sinkhole, devouring part of a the platform (Photo: Sun) |

Repairs on the too far deteriorated train wheels and tracks and a multi-year "midlife" overhaul of the fleet created a never ending array of disruptions, bus bridges and delays. In the early years MTA had begged for money to eliminate the initial cost saving single track sections in the alignment. But the now consistent dual track (except on the spurs) was not used to maintain service when track repairs were needed because of lacking or abandoned crossovers. Train service was stopped entirely in the segments needing track repair and "bus bridges" were established until riders lost patience with the constant upheaval and fled in droves.

The much touted rebranding of MTA's transit services under the name "Link" (as in Bus-Link, Rail-Link, Metro-Link, Mobility Link) did nothing to turn the services around, not even before COVID. On occasion of the systems 25th anniversary in 2017 I wrote an article "Why Baltimore's Light Rail underperforms". All of the reasons I listed then still persist, namely poor land use planning. Today one has to add: Poor management, poor operations and total lack of communication in spite of newly installed technology. The system now is not only dated but unloved. It has lost the trust of riders which is particularly bad right now, when it would be essential to gain lost riders back.

|

| The biggest light rail cars in North America (Photo: Schumin Web) |

The problems have not gone unnoticed. Almost all Democratic candidates for Governor have promised to revive the cancelled Red Line in some way. Editorials in the SUN demand better transit, employers have linked up with the Washington region in order to create leverage for better transit. Reportedly transit played a role in the rejection of the Baltimore-DC region as a world cup soccer venue. Baltimore legislators and transit advocates are working on ways to wrestle the responsibility for Baltimore transit from the State and create a regional transit authority instead.

MDOT seems unfazed. At a recent event of Transit Choices MDOT Secretary Ports was asked about what transit investments were planned with the additional $300 million from the federal infrastructure bill and the $100 million from the State's Transit Safety and Reinvestment Act, He did not suggest anything. Someone asked what about connecting the Penn station spur of light rail also to the northbound service of the system so Baltimore's upgraded Amtrak Station would be better connected to the local light rail? Ports had never thought about it. This full Y connection had been cut from the original system for cost reasons, but could still be built.

Improvement of the ailing Baltimore light rail system will hopefully be initiated by a more transit friendly Governor as a result of this fall's election. The bar is so low, that almost any candidate could raise it.

Klaus Philipsen, FAIA

Note: The writer was part of the design team for the LRT system .1988-1992 and is a member of Transit Choices and Transform Baltimore Transportation.

No comments:

Post a Comment