|

| Complete streets is much more than bikes |

Ryan Dorsey, the councilman who sponsored the Complete Streets bill which is close to becoming law in Baltimore, would agree that the city has its priorities backwards. But he sees the matter entirely different. And he isn't talking about bicycles.

“We are milking cars which will destroy our planet and city as cash cows and use nothing of those revenues to invest into a better future. I think that is morally wrong”Dorsey spoke at an early morning presentation of the Transit advocacy group Transit Choices about his Complete Streets bill and placed it under the larger umbrella of his way of thinking about transportation. He said that the bill is about how we prioritize transportation funding and how "we need to be very deliberate on how we use space". He talked about how employee parking benefits should be portable so employees could use the cash value to use them for other modes of transportation. He mentioned fire-lanes and how the national code for those had mistakenly been applied to all city streets and how another bill of his took car of this. Actually he hardly mentioned bicycles at all.

33% of Baltimore Residents lack access to a car. They rely on public transit, biking, walking, and ride sharing to move around the city. That number is as high as 80% in historically disenfranchised neighborhoods. But Baltimore spends a disproportionate amount of money on streets designed only to move cars. (website)Not speaking about bicycles makes sense, because in spite of public sentiment, complete streets bills are not about bicycles (or scooters) and it isn't about spending massive amounts of money, either.

Instead, the question of how we use the public space that makes up about 30% of Baltimore's entire real estate, is a question that isn't only entirely appropriate, it is also about economic development and resource protection. This question doesn't lead straight to bicycles unless one's creativity and historical knowledge is so limited that one can't imagine anything going on inside the public right of way than driving a car or bicycling. And unless one subscribes to the typical zero sum thinking that what needs to be good for one (mode) must be bad for the other. This type of thinking is obsolete.

THIS TRANSPORTATION SYSTEM MUST BE DESIGNED AND OPERATED IN WAYS THAT ENSURE THE SAFETY, SECURITY, COMFORT, ACCESS, AND CONVENIENCE OF ALL USERS OF THE STREETS, INCLUDING PEDESTRIANS, BICYCLISTS, PUBLIC TRANSIT USERS, EMERGENCY RESPONDERS,Dorsey tends towards hyperbole and maintained that his Complete Streets bill is "the best such bill in the country" which immediately evoked the question, what in his bill is so different than in the hundreds of similar policies across the country? Dorsey's answer: Equity. He pointed out that he heavily learned from one of the earlier and most comprehensive Complete Streets policies in the country, that of Chicago. It was used by many cities as a model to emulate, not least for a very detailed and well thought out design manual. As Dorsey pointed out, though, it missed the social impacts that arise if one uses design as the only lens. He said that the "design framework" needs to be complemented by an "equity framework".

TRANSPORTERS OF COMMERCIAL GOODS, MOTOR VEHICLES, AND FREIGHT PROVIDERS. (Bill)

|

| Many hearings, a good bill (City Hall) |

Passing Complete Streets is one of the most difficult things I've ever done. Our City's streets and sidewalks are truly the fabric of public space that hold our communities together, and this makes them a crucible of competing interests, and a microcosm of our civic life.This law will touch on virtually every aspect of our transportation environment; how it is designed and built, how we prioritize and steward investments, how we engage with community, design for safety and equity, and report outcomes. (Dorsey)Equity is a very popular word these days, everyone demands it, but rarely is it achieved. Dorsey gave examples: How the popular "Vision Zero" (the goal to have no traffic fatalities) policies have promoted three E's: Engineering, Education and Enforcement, but how, in the end, it was mostly enforcement that rose to the top. In several cities, with enforcement the only emphasis, it was directed dis-proportionally against poorer, disenfranchises African American communities where police has always used trivial infractions as a pretext to stop and frisk. Or how bike facilities and expenses were concentrated in well to do areas siphoning off funds to fix hardly passable sidewalks in poor neighborhoods.

|

| Many potshots against a new paradigm |

Back at the Italian Deli, a quick view at the freshly paved street shows that the real money went into a new layer of smooth black pavement. The bike lane in question will take some of the excess street width to move parked cars on the east side of the street 5' or so away from the curb so the parking lane would separate the travel lane from the bike lane. Except for a few extra painted lines, there is no extra cost for this, practically no parking is lost and all the excitement of misplaced spending priorities is misplaced. Hardly anyone would disagree with how much City streets need upkeep to remain passable, benefiting anybody who walks or rides on them, via buses, van, car, bike or scooter.

|

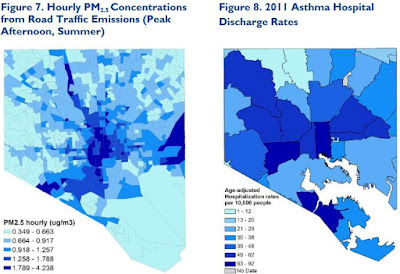

| Traffic emissions and health have a close correlation |

Dorsey's bill includes all the right language and sequence of events, including mandating the creation of an Advisory Committee, design guidelines and even the metrics to be used for those standards, performance measures and requirements for project prioritization and implementation and annual progress reports. Equity is written large over all of it. There are even deadlines by when DOT has to produce public participation models and design guidelines (10 months). What could possibly go wrong?

Baltimore has, indeed, an opportunity to become a leader in a comprehensive public discussion which seriously asks how in the next 30 years we want to use 30% of urban real estate for which demand is high, whether people talk about sidewalks, parking, ride share pick up spaces, delivery spots, bus lanes or bike lanes, not to mention automated robotic vehicles, trees, stormwater management, mail boxes, fire hydrants, outdoor vending or cafes or whatever the future may hold. Aspirations go far beyond the physical, streets affect health, access, and, as discussed, equity. Much to chew off and many reasons for things to not go like planned. Anyone who has lived here long enough knows that Baltimore reality is a tough place for lofty aspirations. Cynicism like the one in the lovely deli is rampant here. But nothing really great will ever be achieved with cynicism. First it takes aspiration and then perseverance and vigilance. If the long journey of bill 17-102 is any indication, there is a majority for those three things in the current City Council.

Klaus Philipsen, FAIA

No comments:

Post a Comment